News Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – DECEMBER 19, 2025

Renee Bourassa, Communications Director

Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin | Rockville, MD

rbourassa@icprb.org | 301.417.4371

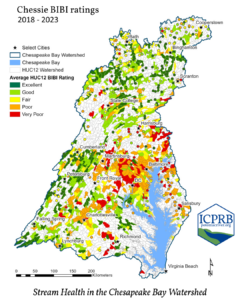

A new report on stream health in the Chesapeake Bay watershed shows a slight improvement in recent years but a strong positive trend over the past two decades.

A new report from the Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin (ICPRB), the organization tasked with assembling and reporting the data, shows a 1.4 percent improvement in overall stream health throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed over the past six years.

The tracking tool is a Chesapeake basin-wide index of biotic integrity for stream macroinvertebrates, known as Chessie BIBI for short. One way scientists gauge the health of a stream is by figuring out who calls it home. Specifically, how many and what species of benthic macroinvertebrates — the scientific term for creek critters like dragonfly and stonefly larvae — are living at the bottom of a stream. Some creek critters need healthy streams to live while others are more tolerant of poor conditions.

“It would be too expensive to monitor for every possible contaminant in every part of the stream,” explains Dr. Claire Buchanan, director emerita at ICPRB and one of the study’s co-authors. “The health of the creek critters gives us a good gauge on the overall health of the stream because their numbers show a predictable pattern depending on their sensitivity to pollution. If something is going wrong — or right — they’re going to tell us.”

The Chessie BIBI tracks percent improvement over 6-year intervals to capture the various monitoring schedules across the watershed.

In the past quarter century, Chessie BIBI has seen which translates to almost 15,000 healthier stream miles overall, according to the report. With the new numbers, an estimated two-thirds of the roughly 145,000 stream miles in the Bay watershed now have Chessie BIBI ratings of excellent, good, or fair.

“Significant watershed management has been underway for decades to the credit of all jurisdictions in collaboration and cooperation with federal, state, local governments and non-governmental organizations,” explains Peter Tango, Chesapeake Bay Monitoring Coordinator at the USGS. “Not only do we get to see habitat changes, but the incredible value associated with the work from consistent long-term monitoring and analysis of the bugs shows us that living resources are responding to those habitat changes in a measurable, tangible, and positive way.”

This measurement is part of the Stream Health Goals of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, which sets a specific goal for the entire watershed. The 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement set a goal to “improve health and function of 10% of stream miles above the 2008 baseline.”

“It is exciting that the partners of the Chesapeake Bay Program could possibly achieve the original 2014 Chesapeake Bay Agreement goal by 2029 if we continue on this trajectory,” remarks Dr. Buchanan.

The Agreement was revised in December 2025 with an eye to the future and a new goal of 3 percent improvement during each interval. While previous intervals surpassed this percentage (4.3 percent and 4.6 percent), the most recent interval fell short at only 1.4 percent. The report notes that data from the most recent interval was impacted by an unusually wet 2018 and 2019 and monitoring gaps due to the COVID pandemic.

“The collection of monitoring data across the watershed is a major achievement, but gaps still remain,” states Dr. Emily Young, a co-author of the report and the habitat and living resources data manager at ICPRB who works in the Chesapeake Bay Program Office. “Some areas have not been monitored in two decades, and a few areas have never been monitored at all. Additional data would help complete the watershed-wide picture.”

In addition to data gaps, improvement is unevenly distributed in the watershed. According to the research, recovery appears to be location dependent, with rural regions showing stronger recovery than heavily populated regions which remain steady from previous years while streams in some agricultural regions are degrading.

“When it comes to streams in the Chesapeake Bay watershed, the biologically rich stay rich and the poor continue to struggle,” describes Rikke Jepsen, an aquatic ecologist at ICPRB and co-author on the report. “This is driving the overall recovery, while the less healthy streams may actually be degrading. It appears that less healthy streams benefit from being close to another stream with a strong, healthy population because they help populate the recovering waterways. This means recovery may be slower in regions that are already struggling.”

ICPRB is currently collecting data for the next Chessie BIBI report, which will cover the next 6-year interval of 2024-2029.

“This couldn’t be done without our partners across all levels, from federal, state, local, and citizen monitoring programs. It just goes to show how working collaboratively across sectors can help improve the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, like the Potomac River,” explains ICPRB Executive Director Michael Nardolilli.

###

PRESS CONTACT:

Renee Bourassa, Director of Communications and Education

Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin | Rockville, MD

rbourassa@icprb.org | 301.417.4371 | www.potomacriver.org

LINKS AND OTHER RESOURCES:

- Report: Stream Health in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, 2018 – 2023 Update.

- Map: Stream Health in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed, 2018 – 2023 Update (JPG)

- More information: “Chessie BIBI” Index for Streams

- Bioregions of the Chesapeake Bay (JPG)

- Online Map Explorer of the Bioregions of the Chesapeake Bay

The ICPRB is an interstate compact commission established by Congress in 1940. Its mission is to protect and enhance the waters and related resources of the Potomac River basin through science, regional cooperation, and education. Represented by appointed commissioners, the ICPRB includes the District of Columbia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the federal government.